The Psychology of Confession

The Physical Effects of the Sacrament and How It's the Opposite of the Struggle Session

We Catholics don’t think much or all that hard about confession. And when we do think about it, we’re rather awkward and weird about it. Part of the reason for this is obvious. The seal of confession on the side of the priest and shame or contrition from our side makes us want to move on after each confession, not to think much about what was said, and rarely to talk about it.

Perhaps that is part of the point of course, but it limits our ability to explain to ourselves, let alone to others, why we go to confession. Sure, we can quote Scripture and the Catechism as to why we do it. Sometimes, we even feel some little internal nagging sensation telling us that we need it. But most of the time, we don’t seem to think, but just habitually go to it.

Maybe it’s because we prefer not to think much about it, to consider it in a very perfunctory, robotic, dare I say—Pharisaical—way. For us most of the time, it’s like a mathematical function (one input, one output). You sin. You “go to confession.” You are forgiven. You do your penance. You move on.

In a certain way, we don’t really need a better answer to “why”. Our sinfulness, our contrition for our sinfulness, and our obedience to Christ’s commands on how to receive his mercy are enough.

But why do we seek forgiveness through sacramental confession? What’s special about the way and manner in which we do it? I am not questioning its primary purpose and effects in applying Christ’s mercy to us to absolve the guilt of our sins, but I will merely postulate some other ways here in which confession helps us, and in which these contrast against the “analogues” for confession found in cults and amidst the Communists.

The Mixed Motivations of the Soul

Let’s start by observing, or reminding ourselves that we’re complex beings, soul-body unities1 who are nevertheless never fully united within ourselves. No matter what we do, as long as we’re outside of the Beatific Vision, we’re bound to have imperfect, mixed motivations. Even Saints were, during their life on earth, fallible and mixed in their hearts as to why they did what they did.

Absent the perfect love of God, lower motivations such as the mere fear of hell are, often, the principles that rule and affect our moral decisions. But what is fear, anyway? What are any of the other similar passions for that matter?

We presume they are bodily, material, sensible things we passively undergo in response to the external world and our place in it. That’s at least how Aristotle categorized them in his Nicomachean Ethics. And perhaps they are.

But the materially sensible is the primary cause for how we, in our incarnate nature as rational beings in a body, come to know everything, and through which we perceive the goods we desire. As the type of creatures we are, all of us, even the orientations of our rational will toward supreme good must be affected by our outer, more material, more irrational feelings and perceptions

Perhaps this was obvious, but it’s a point that must be re-emphasized. The physical and the spiritual meet within us and affect each other. Neither is buffered from the other, yet they meet in a blurry middle ground that we often call the psychological.

We are complex beings, yes, yet our various powers, much like Plato’s metaphor in the Republic of the divided line, exist as a scale, a ladder, think Dr. Jordan Peterson’s frequent references to Jacob’s ladder, or a hierarchy. Lower faculties and powers are more material, more united to matter, less free, and more clearly parts of our body. Our feeling of touch or smell, for example, even as it affects our intellect and reason eventually, is clearly a material power. Higher powers and faculties, like our ability to do geometrical problems or reason about morality more clearly involve the soul, are more spiritual, more separated from matter, and more free (unconstrained by the necessity of matter).

When the physical and spiritual meet, this means, and again obviously, yet this is the main point of Charles Taylor’s massive A Secular Age, physical events, objects, and circumstances affect our spiritual disposition, that is our rational will alongside just our intellect.

Again, it’s what being a material being, a soul united to a material body, is all about. Our powers affect and constrain each other, producing either a dynamic harmony, the lives of the saints and happiness as it would have been classically defined, or something, well, less concordant, and more jarringly jumbled.

With this in mind, things that cause emotions, imaginations, fear, pleasure, joy, anger, etc. in our lower, more material faculties, such as those connected with social standing and prestige don’t just stay here. They affect more than just the relevant lower faculties. They have to affect our higher faculties of reason and will eventually. Moreover, the effects of our lower faculties are the only direct effect, outside of the special and direct Divine infusion of grace that our higher faculties receive. Everything we know and will begins in sense experience. This, including the interior sensation of our passions, emotions, and feelings, is the basis for what we each know in our intellect and desire in our heart.

Of course, the situation is complicated slightly by the fact that grace can operate independently of our lower faculties. God need not only reveal himself through our senses. Yet this is the very way He normally chooses. As much as the Incarnation united matter and spirit, it is in the very nature of the Sacraments that physical, sensible acts and signs be manifestly united with the spiritual reality that they signify.

Restoring the Heart Split Apart

This all suggests that the true redemption and perfection of the soul will necessarily be related to the perfection of the lower parts of our nature. If we focus merely on the psychological state of our mind, again the “in-between” state between the purely immaterial powers of the soul and the materialism of the body, confession clearly provides us some benefits in this area alone.

Confession is Not Just About the Particular Sins

You only know your own faults when you sin through them just as you know your own desires by what you do on the basis of them rather than the story you might tell yourself about them.

Confession, even though we of course confess particular sins, is in the end about perfecting and healing the general orientation of the heart. Each particular sin of ours is but a manifestation of the more root problem within us, our inclinations, yet we only know these through our sins. An examination of conscience, though it measures our particular failings, aims rather more at revealing their root causes. While of course we need seek seek pardon of the guilt incurred by each sin, the real root that needs restoration and healing from the Divine Physician are these root orientations of our heart.

But are hearts are often split within ourselves. We again are neither perfect saints, perfectly oriented toward God, or even ever in a state of perfect contrition, nor extreme sinners, fully oriented completely against God. Even if we’re in mortal sin, and very close to this extreme, God’s actual grace and the twinges of conscience still prickle at us. Rather are hearts are in between God and what is against Him: we’re always at once both somewhat scrupulous and also licentious and tempted to sin.

This is a state of psychological disorder, of a splitness within ourselves, much like that of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov where, raskolnik meaning "schismatic", there is a schism or divide in our soul between our habits and actions aiming at sin and our fearful, conscience-begot, orientation against it.

Restoration

Confession’s psychological help begins here. By providing an objective standard and an objective act, it is psychologically restorative, carving a middle ground between scrupulosity and licentiousness as it sets up a new unity or orientation within us in “contrition.”

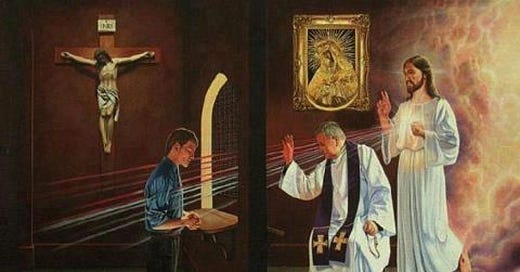

Since contrition is in confession made manifest through a physical, audible act of humiliation, unlike as it is for those others who believe they merely confess to God, and in so doing, are at risk of merely confessing to themselves, it is restorative and reuniting for our psychological selves.

Through confession what was divided and broken becomes in the Sacrament both spiritually reunited through an infusion of grace but also psychologically reunited as the objective, audible act of absolution by the priest

Subjective Experience of Confession

On a psychological level alone, the process of confession, by its structure, builds up contrition to a moment of tension, gathering it into physically sensible shame and social pain before it is then released.

This maps onto our subjective psychological experiences of confession. If you are Catholic you’re probably well aware of this. Subjectively there is building tension within your mind as you approach the Sacrament, and then a cathartic joy-filled “high” as this mental (almost physical) pressure is released following the Sacrament. Often, from my own experience and that of many others I’ve known, it’s almost as if I physically feel lighter when walking away after the Sacrament.

There is of course a difference between the “high” and the spiritual effect of absolution, yet they are usually related. The point is that confession is restorative on all and to all levels of our nature and that we are aware of this, and sometimes even seem to feel it. Of course, if we have true human anthropology, this is obvious. As a body-soul unity, sin corrupts our entire nature, and so also confession and absolution have real effects upon the entire person. What’s interesting is that sometimes (most of the time, for me) we can physically sense these effects.

There is a real danger here if you pursue the “feeling” of confession rather than true repentance. If you don’t get the feeling one day after it, you might scrupulously worry that you missed something—and in a paranoid manner Yet this positive “felt” experience of confession is the proper corollary of contrition, a pleasure at a new internal wholeness that comes from contrition toward and absolution from sin. We are physically changed by confession. For if our contrition is good, we should, in that contrition, walk out with the excitement of a changed heart, ready to sin no more. This, when it happens, is a real effect of the sacrament. Call it a placebo or that we have tricked ourselves into feeling good all you like, but that doesn’t change the fact that something has happened to you and something has changed. Calling something a placebo doesn’t make it not real, at least some of the time. And just something is fake some of the time doesn’t necessarily make it not real when it is real.2 The problem that it might not be real is only a warning to pursue confession for the right reasons and with proper contrition.

Contrast With the Struggle Session

Confession’s redemptive and—for our body and soul—reunitive aspect puts it in stark contrast to the “struggle sessions” observed in cults, amidst Communists and Marxists of all stripes, and any other community not founded in Christian charity.3

Even though in confession we confess particular sins to a priest, receive a penance, and thereby are shamed to some degree, this shame helping to bring about true contrition, shame is not the end state, restoration and peace are, and shame is merely a means. In Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, we read:

Confession diminishes the punishment in virtue of the very nature of the act of the one who confesses, for this act has the punishment of shame attached to it, so that the more often one confesses the same sins, the more is the punishment diminished.4

Here, the writer (not Aquinas, as the Supplementum section was completed by his fellow Dominicans after his death) points out that the act of confession is itself the shame and the end of the shame. The punishment is the act of having to lay bare our brokenness to another. It is hard. It breaks down our pride. Yet it does not break down our human personality in the way that struggle sessions of revolutionary and cult-like movements accomplish.

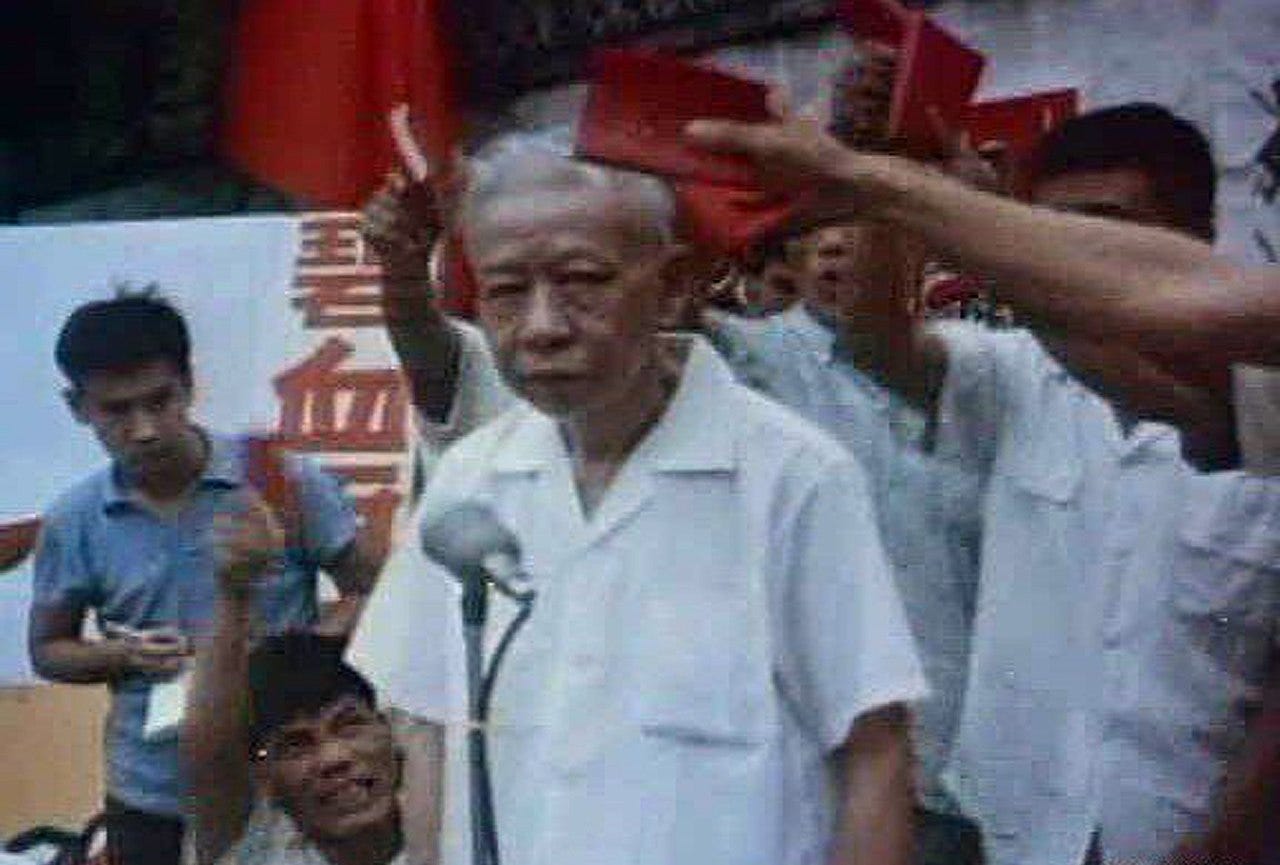

Struggle sessions and show trials, in these movements, were public spectacles where men were accused by their peers, publically humiliated, often beaten, and—although sometimes returned to their jobs or other positions within the community, never truly restored.5 Psychologically the goal is to beat him down to perfect compliance, to drive him into adherence to cult ideology out of fear, to make him a broken man with no agency other than the collective

While confession humiliates the penitent, he as the Summa notes, accuses himself before God and before his representative. Rather than the authority figure within the cult doing the humiliating, the priest’s role is to serve in the person of Christ for restoration to the penitent of his place in the community, of the state of his soul, and restoration of the penitent’s agency through joy and peace.

The victim of a communist show trial or cult struggle session leaves a condemned broken man, remaining an enemy of “the people”, while the forgiven penitent in confession leaves a forgiven, restored man, so restored that he can most of the time even physically feel his new state of peace.

As one political thinker recently summarized it, the “struggle session is a demonic mockery of Christian repentance and forgiveness.”6

I quibble with James Lindsay on many things, but he’s right on this. Totalitarian societies need the struggle session to stay together because fear is their ultimate motivator, and can never rest in any state of peace. The show trials of the Jacobins, the Bolsheviks, and Jim Jones’s “People’s Temple” were necessary for them to amp up feelings of shame and guilt of everyone before the community in order to arouse enough fear to keep their systems going.

Confession may sound like the struggle session, yet even before considering the spiritual redemptive absolution, this profound psychological difference in effect upon the penitents has been what prevents Christian societies from descending into the same cycles of retributive terror that totalitarian unChristian ones have so commonly fallen into. Confession deals with sin in a human way, not ignoring it, but also truly fighting and eliminating it at its root in human pride.

Yes, we are sometimes subject to these flaws in smaller ways. Individual movements within the Church (or claiming to be) go off the rails and begin self-destructive death spirals that often involve infighting, shaming, force, and fear. But this merely provides proof that they are not working of God and for God.

Conclusions

The psychological hump of getting over your own pride to confess your sins to a priest is the difficult part of confession, but that’s the point of how it works. If you can make yourself do that, God can do the rest, and it’s an easy small penance to bear for the rewards, spiritual of course, but also the lesser and psychological ones. This mere “internal shame” or more properly guilt, because of the privacy and seal of Confession, avoids the publically destructive shame of public trials and denunciations. In confession, we attack our pride and are humbled, but do so internally, allowing self-esteem and confidence to be restored immediately in the grace of absolution that immediately follows.

As opposed to the other extreme of dealing with sin and flaws within society, the Protestant “just confess to God” attitude, confession also helps to avoid the subjective error of thinking you have proper contrition without actually having it. Even several Protestants I’ve debated with who disagree with Catholicism on many things admit that they wish they had Confession. If you confess your sins privately in prayer, yes you may have perfect contrition, but how do you know so? Without an objective standard, there is no objective standard for the physical/psychological catharsis to act upon, and no joyous release from tension. In such a situation, since there was no humility necessarily, so also is there no moment for God to work and cathartically by His mercy to release you from guilt.

Yes, it’s difficult sometimes to go to confession, but it’s quite fruitful a use of time. You should go!

Or soul, spirit, and body tripartite beings if you prefer to be more Carmelite, Byzantine, or Scotist. I am tempted at times by this model. Even though it is admittedly far harder to comprehend, it works better in some situations.

Darryl Cooper’s in-depth look into the placebo effect and much more covers this topic well. Just because something is attributed to the placebo effect doesn’t make it not real, does it? It’s quite provocative, and yet, in the end, as long as you interpret the ending in a Christian way, one of his best shows ever:

Darryl Cooper’s God’s Socialist series covers the dark details of struggle sessions in both Jim Jones's “People’s Temple” and the various leftist revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 70s: https://www.martyrmade.com/featured-podcasts/gods-socialist-the-rise-and-fall-of-peoples-temple

(Note: the Supplementum was written by Aquinas’s fellow Dominicans after his death) Summa Theologiae, Supplementum, Q.10. https://aquinas.cc/la/en/~ST.IIISup.Q10.A2

More dark details here: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=33200

per footnote 1: James! you're not a tripartitist?

James, you’ve got me!

I keep telling myself that I need to go but always find some excuse, the line is too long, I’m not comfortable with that priest, I haven’t done anything really seriously wrong since I quit drinking, I can’t miss my AA meeting, … the list of excuses goes on and on.

I hope the encouragement you provided will outweigh all my excuses and get me there this week!

Thanks for the (slight) guilt trip, I needed it.

Regards, Andy