Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

- Robert Frost

We decide and desire things, like choosing to take one path over another, but do we ever stop and wonder why we chose what we did? We presume our choices are “ours”, but why did we make them? Why do we desire what we desire? Who decides our desires? We presume ourselves, but what does that mean anyway?1

Free will is one of (if not the) most important questions out there. For if we don’t have it, if our actions aren’t really ours, then nothing matters. Literally. If it doesn’t exist then the murderer isn’t to blame for murdering any more than the Blessed Mother is to be praised for her holiness in cooperating with God. And so, free will has been the biggest question bothering me for at least the last two years. Do we have it? What is it? What are its limitations?

Leaving aside the fact that we don’t often stop long enough to think about what these words mean, we live with the presupposition that we have free will, even if we profess ideologies like material determinism or double predestination that seem to deny it. We don’t even know how to begin investigating this hyper-important question. Instead, we live with a cognitive dissonance of living as if something is true without knowing for sure what it means for it to be true or how to decide whether or not it is true.

In particular, this dissonance is revealed by most arguments for or against free will, obfuscating the real question(s). Nearly everything I’ve read about “Do we have free will?” seems to be asking instead, “Can a person’s behavior be predicted?”

Asking this question freezes the inquiry into a hard binary of physical determinism.

If (1) the physical world operates according to deterministic laws, then human behavior can always be predicted in advance, and free will is an illusion.

If (2) the physical world does not operate according to physically deterministic laws, then human behavior, like all other things in that world, cannot be predicted in advance. According to this view, free will:

(2a) either still does not exist, and indeterminacy or randomness like that proposed by quantum mechanics in the nature of physical law is the cause of indeterminacy with regard to human actions, or, on the other hand

(2b) or free will exists and is itself the cause of why the physical world is not deterministically predictable.

But in this way of framing the question, the one path (2b) that does allow for free will leaves no possibility for it to ever be defined or explained. Free will, considered this way, can only be defined negatively, as an inability to predict what course of action some man or group of men will take. And, perhaps that is all that can be said. Perhaps humans are free because no other human can predict what they will think, say, or do. But I dislike this lack of precision as this fuzzy definition of free will leads very logically to the denial of free will. Without some positive clarity on what a free human act actually is, there is nothing to say that it actually is free. The only intelligible alternative, if you regard the subjective experience that human behavior is not always predictable, is (2a) that randomness in the character of physical law leads to unpredictability in human behavior, but that there is no mystical concept like freedom.

Even belief in the non-physical soul doesn’t seem to help. One could posit that the soul, the rational faculty of the will is the cause of human freedom, and, the argument goes, is free because it is unconstrained by the material necessity of physical law, this power of the soul does not have to settle for one course of action over another, and is therefore free. But freedom here is still defined within the frame of the question of predictability. Why, one who inquisits further, might ask, does the will settle on the course of action that it does? Well, you say, it doesn’t have to do x and could do y, but it does x, and therefore there is freedom. But adding the soul to the investigation hasn’t helped explain what free will is, only reduced the discussion of a free being to discussion of a free faculty of a being. And it is still only defined negatively. We remain locked within the negative definition of free will in terms of predictability. Free will remains, it seems, as an unpredictability in the course of human actions, and the most positive way in this frame I can think of defining it, the ability to flip-flop, still seems not much better than ascribing as in argument (2a) above, everything to randomness.

I haven’t and won’t address the other set of objections to free will, divine foreknowledge and predestination,2 but as it seems to me, the restricted way the question is usually addressed leads to issues with any stance you try to take. Either you take a simple free-will-denying view that is understandable and intelligible or you affirm freedom without really knowing what you are affirming.

The Proposal

This confusion occurs, I believe, because of a misconception that the essence of free will is unpredictability, that man is free because his actions are unpredictable and he flip-flops. I hold, rather, that human behavior can normally be predicted, but nevertheless, free will still exists, and although its operation is far more limited than we might implicitly assume, it has a simple operation and definition.

Free will, I propose, is not the ability to unpredictably flip-flop, nor to choose a course of action without externally determined or inborn reasons or causes, but to accelerate at each moment in desire and motive towards one course of action over all others.

To see this, I want to first emphasize how little freedom we do have, how much, that is, our desires are not decided by us in a vacuum.

We are not unaffected by the external world. Things out in the world, unchosen and unchangeable facts about our own disposition, as well as other people almost completely control our desires, and through them, they also almost completely control our actions.3

Think about it. Why, for example, did you desire to eat today? That desire came from an inborn drive within the human nature you possess. That desire was not decided by you but affected you. Why did you decide to take up rock climbing? Well, some part of the answer is an inborn drive for excitement, exercise, and adventure. But here, much of your interest and desire came from friends introducing you to the sport. Why do you dress the way you did today? Partly out of inborn desires (it’s cold and I don’t want to be cold today) but probably mostly out of a desire for conformity to people around you whose style you like, in other words, mimesis. Why are you voting for Candidate X over Candidate Y? Much of it is probably determined by what information you have received and what information you have not about the current political issues and the candidates. But the deciding factor beyond this, taken several steps back, is not an entirely free and independent choice on your part either, but based on your upbringing, the beliefs of your friends and peers whom you wish to fit in with, etc., again factors beyond your direct control.

However, against the seeming complete dependency of our actions, and through them our desires upon things beyond our control, I believe we have a small modicum of freedom. I can not prove it. Again, this is not a full proof of free will. You believe and know you have free will from your own experiences, not from a deductive process. I believe freedom has a real external effect in which our outputs (actions, words, influences on other people, and external objects) differ from a mere sum of the inputs (forces acting upon us and our desires) on each of us.4

Our outputs could differ from our inputs by being entirely contradictory to them. Such is the theory of free will as the ability to flip-flop, to act and desire in an entirely contradictory way to how you desired a moment before “just because you are free.” But I do not believe that that stands up to the evidence of experience. No one does something, even in the extreme cases of the psychotic murderer or someone committing suicide because it is against their willed desires. Everyone does things because their actions, thoughts, and desires, having formed a continuum of experience up to the moment, have in each moment leading up to a potency for the actions they are about to take.

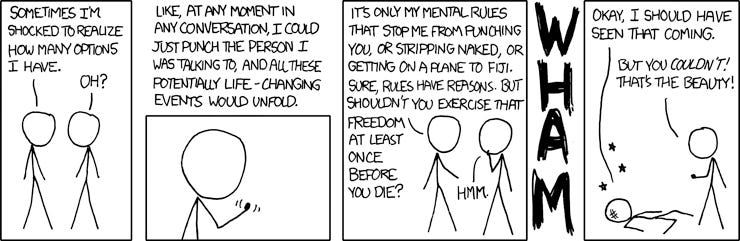

In likely contradiction to this XKCD comic below, unless punching your neighbor was already in the range of things you were willing to desire to do, you won’t do it, even just to exercise freedom, because your inputs up to this point have made you the type of being who responds in a certain way, hopefully more courteously than the character in the image below… However, you are the type of person to whom responding by punching back is a possibility; well, tautologically, based on your past inputs, desires, and habits, it is a possibility.

Using Calculus to Understand Free Will Better

But this does not mean that human actions are necessarily fully constrained by past inputs. There is one other way in which outputs can differ from inputs. Let’s consider your life, actions, and behavior as if it is a place on a coordinate plane. The sum of your habits at one point in time is like your place on the map. At any one point in time, it is definitionally static. You are now what you are now. However, your position on the coordinate plane changes over time. Where you are now, what you desire, and what you do based on those desires can change. As we’ve discussed above with the inborn disposition and external factors such as mimesis, most of this change seems to be due to such unchosen causes. You cannot induce a change in location by yourself. These unchosen factors are analogous to motion or momentum being imparted to you from the outside. They, in this analogy, change your place in space and push you in a certain direction on the coordinate plane. They, in our world, are the desires we do not choose that push us towards one course of action or another. Again, we do not yet perceive freedom.

But let’s differentiate; let’s consider the derivative of motion or momentum. In calculus or physics using calculus, differentiating momentum or speed gives you the acceleration or force acting upon you at each moment to impart the change in motion or momentum, the rate of change of your motion over time. On the coordinate plane, this is how external factors affect your motion and, through it, your position. For example, the action of gravity on your height above the earth does not impart an instantaneous acceleration from 0 to 100 MPH. You slowly, and not instantaneously, speed up as you plummet toward the earth, for example. In human behavior, similarly, an external force like peer pressure does not act to instantaneously change your desires. Rather, external forces change our direction and desires but do so over time by slowly accelerating us from one course to another, a small change building up over time to a complete change in personality and direction. And again, this seems to be more ammunition against free will.

However, the external inputs affecting us do not blindly have to equal our actions and outputs. What if, how you respond at each moment to the forces acting on you at each moment matters to the outcome of how you will behave in the future? At each moment, I believe, you can lean into a desire entering you from the outside or lean against it. Whilst this will not instantaneously change what you will do in this moment, this reaction at the level of the double derivative, the rate of change of the rate of change of your disposition and habits, is a completely self-driven ability to have different responses to all the factors affecting you.

Ok, what does this mean practically? Suppose you are pondering whether to exercise today. In your heart, you are split. Part of you desires to run, and part of you doesn’t. The pressure of a friend to go out and run with him bears upon your desires. But so also does the desire that pops into your mind a moment later to stay inside and read a book does also. Each external force influences you, and you are not in the moment responsible for either desire. But how much you respond to, how much you lean into or lean against the first desire, or how much for or against the second accelerates or decelerates the impact of the external causes towards your ultimate decision. You did not decide your desires, but you decided how you responded to them.

For another example, suppose you have just committed a sin. At the moment in which you sinned, it was in your behavior and habits determined up to that point in time to commit the sin. But how do you feel about it afterward? Do you lean against those tendencies that led you to it or against them? How do you feel about yourself? All this affects how you will respond to such forces in the future.

And so, I propose that man’s freedom is heavily constrained, yet still exists at the level of the double derivative. How we respond to the desires we have not chosen yet experience, and which are still yet our desires, is the modicum of freedom which we exercise at each moment.

It is a faculty of accelerating or decelerating, cooperating with or fighting the external forces affecting you at any particular moment. Free will is in every moment, but its effects are about the future, not for the moment you are in, or even the immediate future.

Thus, human actions, I believe,e can be summed up by three factors:

Inborn and unchangeable psychological drives

Imitation/Mimesis of Others

Freedom on the derivative of desire (i.e. we can affect how much we desire and how fervently we pursue something, but can not create or destroy a desire ex nihilo.

We are in no way independent and self-existent beings, but we are players, and we are free.

In this view of free will, your behavior can often be predicted. I think this makes sense and is not contradictory to free will being real. If you are behaving rationally and in your own enlightened self-interest, yes, someone who also knows you well, could predict what you will do. In fact, predictability and interior consistency, in some cases, are actually the greatest proof of freedom.

The Martyrs are the Most Free

Consider, for example, the case of the martyrs. If someone merely reacted to the forces and conditions of the moment of their passions, the threats against their earthly existence and material body, they would cave in and apostatize. But the fact that the martyrs did not, that they held firm to their interior conviction and devotion to die with Christ, shows an ultimate freedom to act against the whims and conditions of the moment. That the martyrs held out in love of Christ to die like and with Christ was the product of a long chain of choosing to love (and cooperate with grace, but I won’t get into Pelagianism and the more theological side of all this here…) at each moment in their life. A long chain of moments of exercising love for God brought each of them here and was confirmed by a final free act of exercising freedom, persisting according to the virtue of devotion in him, even unto death, the freest, in fact, of deaths.

This view of human free will also suggests that it is possible to refuse to exercise freedom, to impart no additional acceleration or deceleration in response to the different pressures bearing upon each of us. Such is the case of the weak man, the completely mimetic man, the crowd follower, and pleaser, who is in the habit of not exercising freedom and rarely does. He does not impart continuous acceleration in one direction or another of the various potencies possible for his future. He wavers. He blows with the wind. Such men, can perhaps still be free at any moment, but are paradoxically, freely not exercising freedom. Their behavior is thus also free and predictable most of the time, as it can be predicted by measuring the external inputs and pressures bearing on them. Such men are the NPCs of current meme lore.

The External Analogy

Another way to demonstrate our limited but still extant interior freedom is, I believe, by way of an external analogy.

I believe that as is the case for a man to affect his chosen path and chosen desires internally and personally, so also is his freedom to affect history externally and on a large scale. To show this, let’s look at how men can affect history.

I believe that the trends and forces theory of history is almost completely true. Most individuals merely react to and imitate the trends around them. A soldier caught up in World War I isn’t doing much to change the overall outcome of one of the battles, let alone one of the fronts. Even a general can’t do much on his own. If he wasn’t there, someone else would likely have taken his place, observed the same facts on the grounds on which he was basing his decisions, and, if similarly trained and educated, would likely have made similar decisions leading to similar outcomes. Most of the time, trends, beliefs, or lifestyles that captivate millions are the primary actors in determining a historical outcome. A powerful individual being present or absent from a generation doesn’t usually change them that much. Nationalism seems destined to be the unifying story and conflict of the 19th century as much as communism that of the mid-20th or German revenge against the Treaty of Versailles of the late 1930s, regardless of how many of the players you change out within the course of each period. Such forces either subsume the individual or a countervailing trend present at the same time will subsume him.

There are thus no singular turning points in (regular) history (except for the Incarnation and Redemption). History is always a swirl of different forces responding to each other by acting upon and taking hold of individuals. But these trends and forces, while immutable and inexorable within their own time, are the way they are because they “gained steam” and became powerful at some earlier time. Men cannot create or destroy historical trends completely ex nihilo. Marx’s theory of communism, for example, did not come solely from him, but by him coalescing and giving force to existing in his intellectual milieu. He did not create communism but imparted acceleration to the ideas that became communism. Lincoln did not bring about the Civil War ex nihilo. It probably would have happened without him. But he accelerated certain trends and accelerated certain others by way of his words and actions that coalesced events into those that did befall the United States.

In other words, man’s freedom to affect events in history is predicated on his response to trends, either accelerating or decelerating their force upon others. Any one individual on their own is not going to get Trump elected in 2024. But one individual can affect the desire and energy in others for the Trump candidacy.

There are some outliers, like Alexander the Great, Caesar, Napoleon, and perhaps, in our day, Elon Musk, who all seem such a departure from the milieu around them and so consequential in their own actions that they have created historical trends. But these men are quite rare, and perhaps over the long run, they, while seemingly affecting history inexorably in one direction, perhaps did not really do so, as they indirectly may have provoked counter-reactions to their actions which bring their net impact of history down below what if may seem.

But the point here is to show that by analogy, a man rarely affects the large-scale trends of history by himself, and so also, in like manner, his free will within himself is also limited to merely accelerating or decelerating his responses.

Conclusions

I have other thoughts about free will and its powers and limitations, which I hope to cover soon. However, my main point is that persistence and not unpredictability is the measure of freedom and that freedom is limited to our measure of response in each moment to external forces in that moment.

Does this mean anything groundbreaking practically? Probably nothing that has not already been said in other words by other people, as in Jordan Peterson’s practical injunctions that large changes in our own lives must begin with small steps. Our freedom is less visible from moment to moment than from year to year under this view but remains quite limited even then. We are forced, when considering our own future, to reject the unmoored perspective of “be anything.” We really cannot be anything and cannot really desire just anything at all. We will be limited by things that have not been decided by us. All we can do is grow in self-knowledge about our own potentialities and steer towards the best possible of this subset.

At the very least my idea does not contradict the Church’s teachings on cooperative grace, as, in effect, I’m only proposing that free will acts within the limited bounds of cooperation with or action against grace within each moment.

Again, I also do not propose to have proven free will, but just to explain how it would operate assuming it does exist. If we don’t have free will, there’s no point in worrying about it or anything else for that matter. In that case, we are all NPCs and can’t not be one, and can’t blame anybody for anything they do, nor praise anyone or ourselves for anything either. But if free will does exist, it is at least important to understand what it really is and is not. Mysteries remain. What is it in us that leans in towards and accelerates a certain response? We’re calling that thing free will. And that’s all I’ve proposed to do. If we had a perfect, unmysterious definition, it probably wouldn’t be freedom.

This is a slightly updated and revised version of an earlier post that was written when my Substack was far smaller, so it should be new to almost all of you.

Christian Wagner of Scholastic Answers has a great video on the Church’s teachings on predestination:

As does Fr. Ripperger:

The Catholic Church actually does hold to double predestination, but just not exactly in the way that Calvin and the Calvinists do.

As in the thoughts of Rene Girard on man’s proclivity for mimesis as recently popularized by Luke Burgis and Peter Thiel amongst others.

In the same vein, spiritual reality (realities) have a real impact upon us as persons and, therefore, also upon our behavior and material reality. More on that to come very soon.