Why do you want what you want? If you’re an adult with a career, why did you choose it? Or, more properly, why did you want it? If you’re a “youngster” with a passion or interest, what made you desire that?1

Rene Girard’s theory of mimetic desire, and common sense and personal experience agree on an answer. You aspire to what you perceive as being desired by those you respect. Not many of us aspire to be candlemakers anymore, let alone hoplites. But many of us wanted while growing up—or even now—to be successful businessmen, inventors, or sports stars.

It is the nature of our will, Girard proposes, that we desire high-status positions and careers in society because they are things that other people want, and which, importantly, we observe them “to want.” It is how envy is for Girard the worst of sins, as it is mimetic desire gone wrong, and the source for him of all conflict within societies. The 10th Commandment, is, at least on a natural level, for Rene Girard, the most important, as it is God’s injunction against undue mimetic desire and its correspondingly destructive envy. Most of the time, however, mimetic desire is for him, subtle, and yet very influential when it comes to the ultimate orientation of our wills. To a degree, within Girard’s theory, those around us decide our desires for us by our will naturally orienting toward those things that we each perceive as “in demand” or “glorious choices” by those around us.

For Dostoevsky, similarly, as he most expressly argued in The Brothers Karamazov, this is how and why we are all guilty of all before each other as we all are causes of what everyone around us desires or fails to desire properly. One twist should be added: local influences, those people who are closer to us, like our parents or close peers, probably have affected us more than the general desires of our broader society. Many of us choose our careers based on the work our parents did or fields or paths they showed interest in yet didn’t make it to doing themself. On a base level, merely seeing a good thing, and seeing people we respect talking about it positively creates interest and demand in it for us by that very sake alone.

The Vocation Crisis?

Applying this observation conversely, it is also likely that most careers, or well, vocations, that it seems are lacking in interest today, are unwanted, undesired, and unchosen precisely because there’s not enough sight, knowledge, or positive talk right now going on about such things.

It’s not much of a novel claim to make, but if aspirations are mimetic, and not having such aspirations is because of a lack of mimetic example, an easy solution to the vocation crisis in the Church would be exposing the young more to religious vocation as a “normal” thing. LGBTQ…(?) activists know this. That’s why they go after the young so forcefully and predictably with their attempts to “normalize” such behavior within malleable young minds.

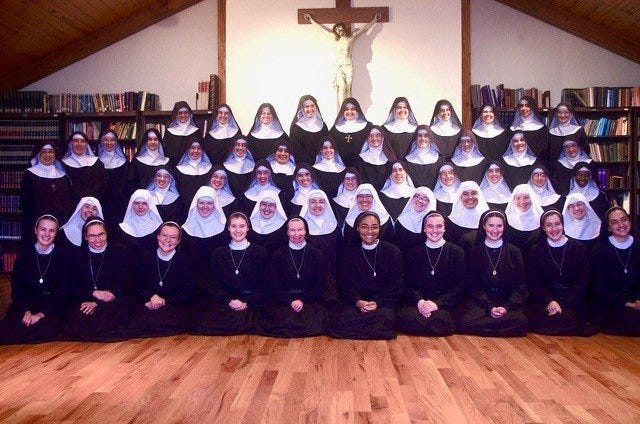

However, I also don’t think it’s as simple as just exposing young children to just any monks or nuns. Take two monasteries from near where I live as examples and see what these images make you think:

Please don’t get me wrong. I am not trying to be agist or disrespectful. The natural—and perhaps sad—fact is that we all are agist without trying, especially as children. When it comes to mimesis and how our wills are moved to desire a course of action, we respect elders, yes, because they have status and success, but we are also naturally drawn to youth, vigor, vitality, and the outward appearance of health.

To children, I’m sorry, but neither the above images of the religious themselves nor the dental office-like appearance of the newer buildings of these two once vigorous but now dwindling and aging congregations inspire much aspiration. Paradoxically, it’s not that there’s something unpleasant and unappealing about the, well, “more liberal” and loose congregations. The problem is just that, along with being old, and seeming to be dying institutions closing off monasteries rather than growing, they’re too vanilla and too bland.

Where’s the glory in giving up marriage, family, and the world if you’re going to dress like the world, live like the world, listen to music like the rest of the world, and not really be all too separated from it in the way you live other than a much condensed Liturgy of the Hours, a few limitations, and living in a dying institution that’s glory days are, obviously, behind it? What are you aspiring to, if you were to desire it? Well, bluntly, to be part of something in decline and dissolution? I’m oversimplifying of course, here, but let’s start by asking why we, and especially the young, think this way.

Bubbles and Spirals in Desire

The action and growth within us of our desires often is like a financial bubble. External appearances matter more than inward reality. When we desire something, we have to begin by desire acting as if our interest in and capability for satisfying our desire is far more pure, grand, and certain, than it really is. By beginning to desire something in this way, however, our very desire begins to perfect our own motivations and make what was once a bubble expanding beyond reality into a firm and steady conviction, a bubble that solidifies and doesn’t pop.

When it comes to religious life, or, for a similar example, military service, a virtuous upward leading spiral that eventually turns one into a saintly monk or warrior Marine has the best chance of being desired if it is marketed to the young with a combination of both relatability and difficulty/grandeur. At once, the end must be glorious, exciting, difficult, and sure to give you prestige and high social status. But it must also be relatable. The young person must easily be able to imagine themselves turning into the glorious, confident, and proud warrior portrayed. Military ads rarely show pictures of old people or grizzled veterans for the obvious reason that these ads don’t work as well when it comes to inspiring young men.

An ad cannot be too relatable, again, because the end isn’t that much different from where someone is right now. “Put on a uniform and do nothing but sit in the same type of office you did last week?” I’m sorry, but that just doesn’t inspire much of anything. Where’s the esteem in that?

Only a combination of the two works, and does so by presenting glory and then showing you how you can get there. What comes immediately is a bubble where expectations, desire, and self-imagination shoot upwards past one’s real current state. What comes later is the hard work where one really does become the glorious thing portrayed and achieves a real correspondence between desire and reality.

If the goal is made too easy, where’s the glory and reward in achieving it, so why bother? It’s more paradoxical with Christianity and religious vocation because we think about less in this way, even while the military example probably makes some sense to us, but the same applies to them as well. Douglas Hyde, a former Communist Party propagandist who later converted to Catholicism, pointed this out to great effect in his book Dedication and Leadership. Being told that Christianity means merely, “Come help stack some chairs for the coffee and donuts after Mass” or becoming a nun doesn’t add many requirements nor mean much of anything, makes both into bland, uninteresting, inglorious choices. Making only small demands of people creates a death spiral in people’s interest and desire for a mission, Hyde argues. Large, potentially impossible goals and massive requests, as he noted from his own experience with the British Communist Party, by contrast, get results. People want and are motivated only by glorious, and yet just barely possible, purpose.

And so we shouldn’t be too surprised when few young people aspire to these, especially when all the monks and nuns, and many of the priests they see are all old, often sad-faced liberals some of which don’t even seem to love all the time the Church they serve (I’m overgeneralizing of course, but to make a point).

So, what’s the solution?

In some way, it’s obvious. Exposure to monks, nuns, and priests who are young, enthused, and, also, well, living differently and gloriously from the rest of the world does a lot to inspire aspiration for that life

Compare the former portraits of declining congregations to this image of the nuns at Abbey of Our Lady of Ephesus in Gower, Missouri:

Or to the monks at Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma:

No explanation is needed. There’s an entirely different, and far more inspiring “aura” projected from the images alone, one of youth, health, vitality, and glory, let alone the actual experience of visiting and meeting the monks and nuns therein.

Ben & Tryson — The Catholic Intelligence Agency

But just how well does this work to motivate young people and what do these aspirations look like within them, practically speaking?

This is not a statistical article, so I’ll be ending with an argument by (hilarious) anecdote. I will point out that the more demanding, more traditional, and younger religious orders and congregations all happen to be the same few places. The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter gets multiple times the number of serious applicants than their Lincoln, NE seminary can take, the Benedictine nuns of Gower are overflowing even as they form three new foundations for daughter convents near simultaneously, and the Benedictine monks of Clear Creek are very young and also highly overflowing with vocations.

I spent several weeks across two visits last year to the Benedictines of Clear Creek myself (leaving after being told that at least at present I do not have a vocation with them).

Both times, however, when I was visiting—they were overflowing with young men visiting them with more or less serious vocational interests all the time—I met some really young people.

Two in particular stood out. During brief post-meal times of recreation and conversation following meals with the monks, I spoke with Ben and Tryson, two close friends aged 17 and 18 who were making their first solo, that is, apart from their parents, visit to the monastery. They had visited many times before, were each one of about ten to twelve children, and each had several older siblings, both their brothers and sisters who became priests, monks, and nuns at various other places around the country. Interestingly, they came from near the Abbey of Our Lady of Ephesus in Gower, Missouri, where they (and their brothers) are the chief servers, have multiple relatives who are sisters there, and visit all the time.

Ben and Tryson were your typical teenagers, ok, to be honest, in the homeschooler, that is innocent and yet hilarious, jovial, and yet bitingly satirical kind of way. They both are discerning religious vocations themselves. And yet they approach religious vocation in an upbeat, vivacious, or perhaps the best word is “chipper” kind of way.

Whereas other kids their age debate their favorite video game characters and power levels, Ben and Tryson, while I was working with them one day on the abbey grounds, spent the afternoon debating which religious name they would take and who would get to take their first vows first. Whereas other kids know (or at least knew) just about every sports star in the country, Ben and Tryson seemed to have an intimate and detailed knowledge of every order, every monastery, and even many dioceses in the country. I could name someone I knew who had entered an order somewhere in the country and they could immediately rattle off their religious name, their date of profession, and their prognosis for taking their next phase of vows. They also knew the biography of just about every saint, including those I had never even heard of, the ecclesiastical calendar perfectly, and had the Latin Mass perfectly memorized.

I called them, and only half-jokingly, the Catholic Intelligence Agency (CIA), because that’s what they were. The Church, and religious vocation in particular, was what they aspired to, and because of that it filled their minds, it was their obsession. Of course, they also knew a bunch about hunting and particularly did bemoan the fact that deer season opens the same day as the extra long Mass at which nuns at Gower make their professions.

Of course, this is a very special case. Ben and Tryson’s parents each made the decision to live close to the monastery at Gower, and in doing so, Ben and Tryson had about the most opportunity to be close to religious and priests and learn all these details for their entire lives. Few can have this level of exposure.

But when it comes to Ben and Tryson and their friends from back home, it’s clear more generally that one simple way out of the vocations crisis is making religious vocation relatable and more glorious by just being exposed to it a bit more. There certainly is no crisis within either of their families, and it’s not, I don’t think, that God merely calls from a few certain family lines.

The difference is that the parents of these two young men I met chose to expose them to those orders and monasteries that succeed at looking both relatable and glorious. Of course, there are potential pitfalls of false vocations, as I believe did occur somewhat in the Middle Ages when perhaps religious life was pursued sometimes for lower reasons of glory—and at times, wealth—alone. However, due to our natural passions, our natural imagination, and the complex interplay between natural and supernatural, God’s call must act and operate upon our imagination and lower desires in order to succeed at drawing one up into the supernatural, extraordinary state that is a religious vocation. Our love for God must begin in lower desires that are slowly perfected over time, as I’ve pointed out again and again in this publication, and if we blunt or filter out these lower aspirations from even starting by not being exposed to religious, we shouldn’t be surprised with the outcome. But when you are exposed to young, traditional, fervent, growing communities like these two young men were, you can’t help thinking about, and if God is calling you, you’re certainly primed to respond: “Yes Lord, your servant is listening.”

Not every Catholic family needs to live in Gower, MO or Hulbert, OK. There are lesser ways of exposing the young to religious life and activating the opportunity for them to mimetically aspire to it than moving to those incredibly small towns. Just visiting a solid, fervent, and traditional monastery or convent, and praying and working with the monks or nuns is a good start, and a good thing for every teenager, even if they never have a religious vocation. But there’s certainly no vocation crisis where Ben and Tryson come from.

See my full, Girardian theory of free will here:

I think there's an issue of economic and cultural shifts as well: our society is becoming more bureaucratized, more managed, more safetyist, more fragile. I call this 'feminization,' although it's not a perfect label. The traits that are rewarded in this scheme are organization, emotional dependence, conformity, consistency... not initiative and courage and restless energy. \

That's actually why I chose to call this meta-trend 'feminization'-it perfectly suits female workers, and generally penalizes male ones.

https://jmpolemic.substack.com/p/job-search-part-4

Hello, I am new here. This reminded me of a conversation I have frequently with a former nun in my scripture study group - she loves that they took off the habit and I say it was a terrible idea.