State of Necessity?

The Real Effects of the Priest Shortage, The Managerial "Solutions", and the SSPX

Among the reasons for the corporatization of the Church, the infiltration by managerialist methods and motives that prioritize process over product and organization charts over the faith, is that handing over de facto power and administration in the Church to lay administrators, turning the bishops into middle managers, and cozying up to governments was actually a rational response to the problems faced by the Church after the Council.

With a massive decline in the religious orders, an increasing shortage of priests, and many of the most faithful participants and members of the Church having been filtered out after the revolution, a turn to increased managerialism and secularism was the solution that beckoned, even for those who weren’t modernist ideologues.

Rationing Managers

If you don’t have enough nuns to run the Catholic schools, nor enough lay involvement to keep the local parish running, nor enough priests to minister in every parish, you move the goalposts by closing Catholic institutions and parishes, or prop up those that remain by allying with governments, and subtly—or not so subtly—changing their mission.

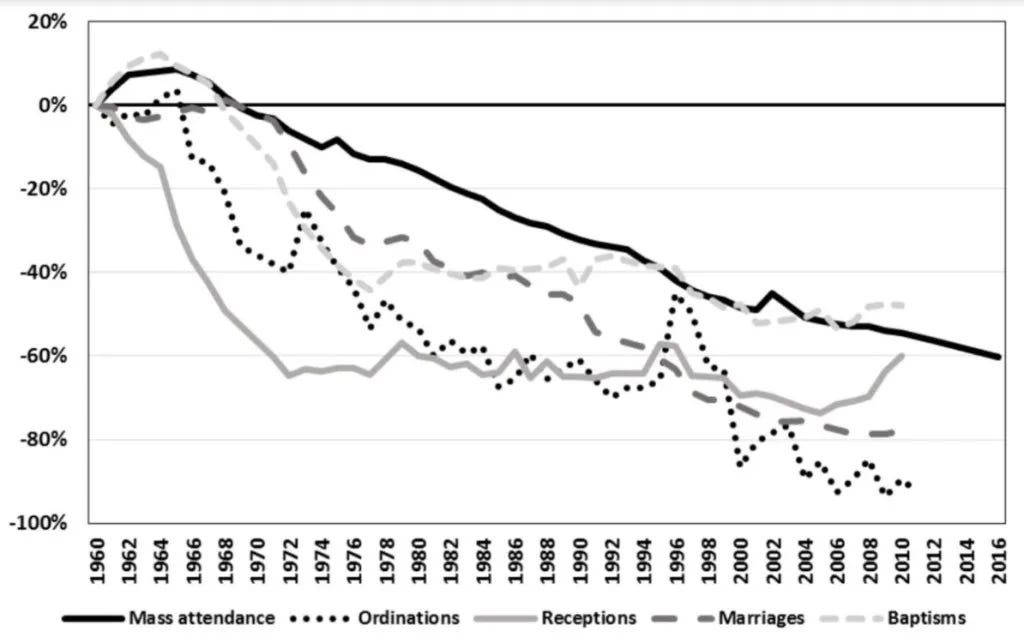

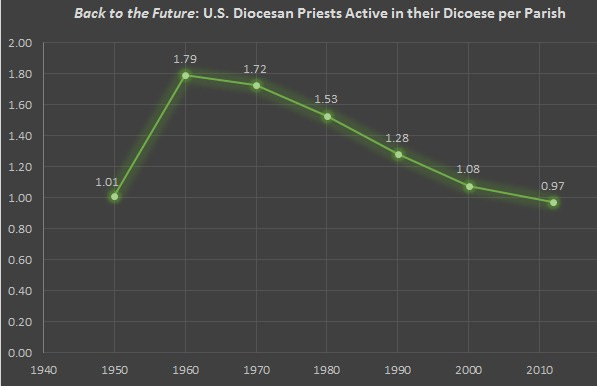

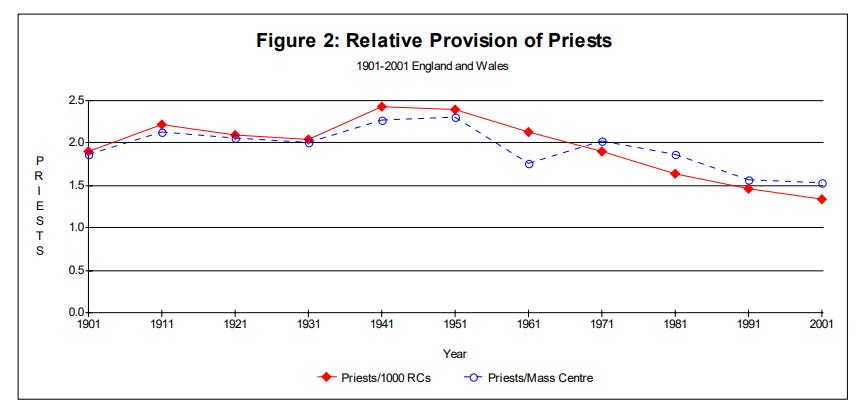

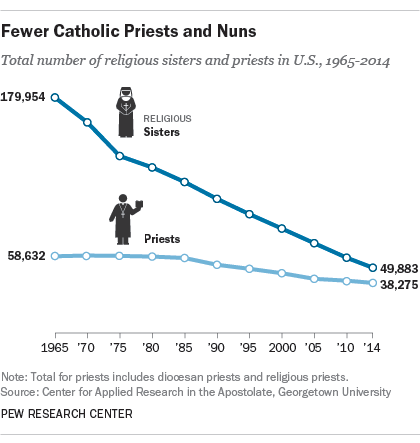

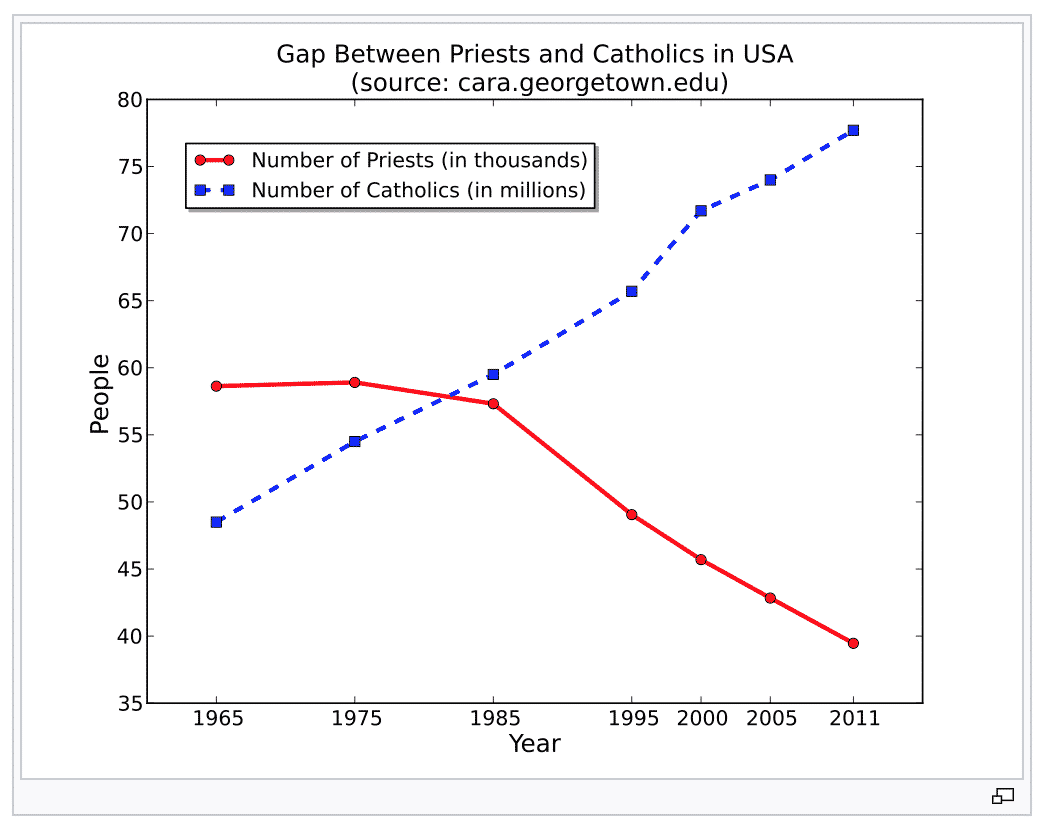

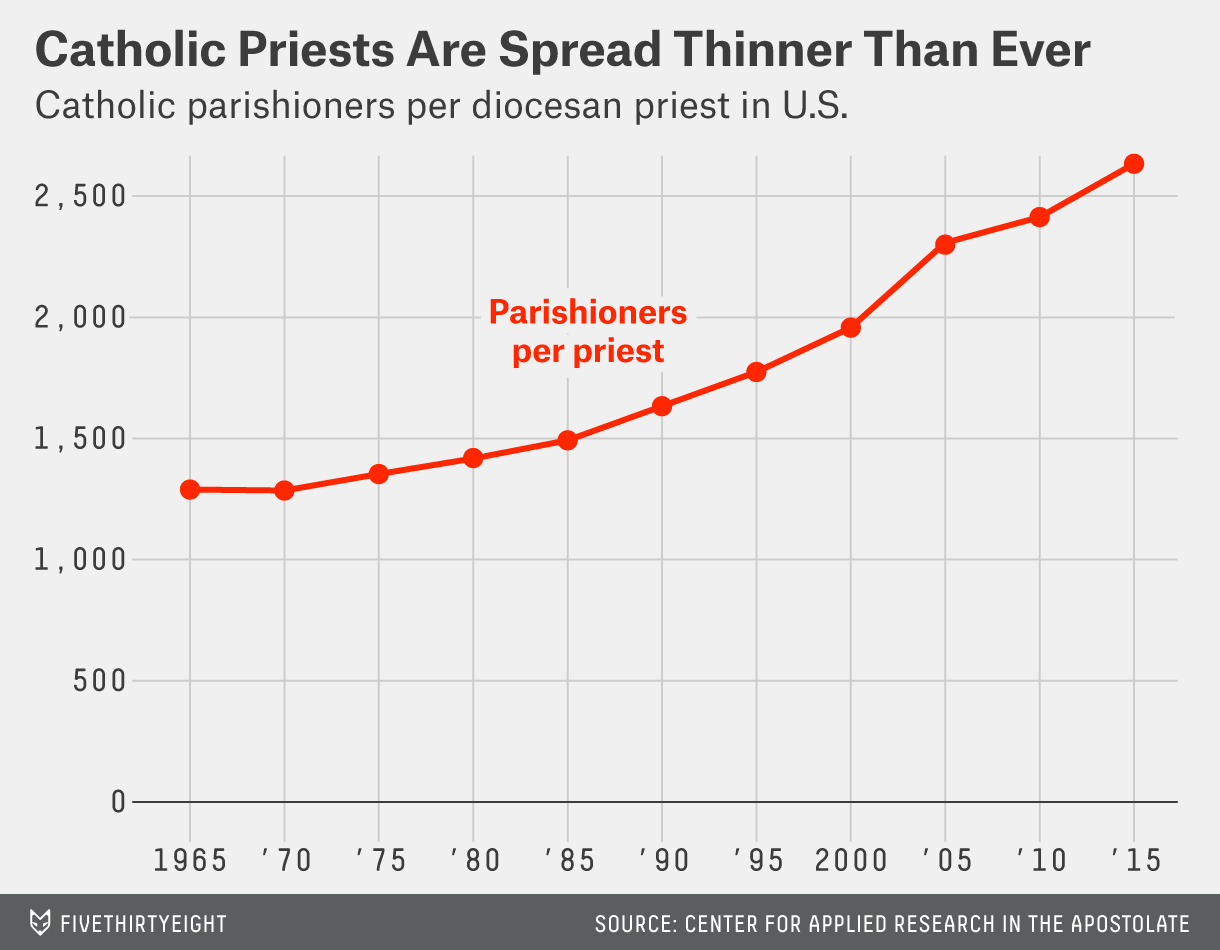

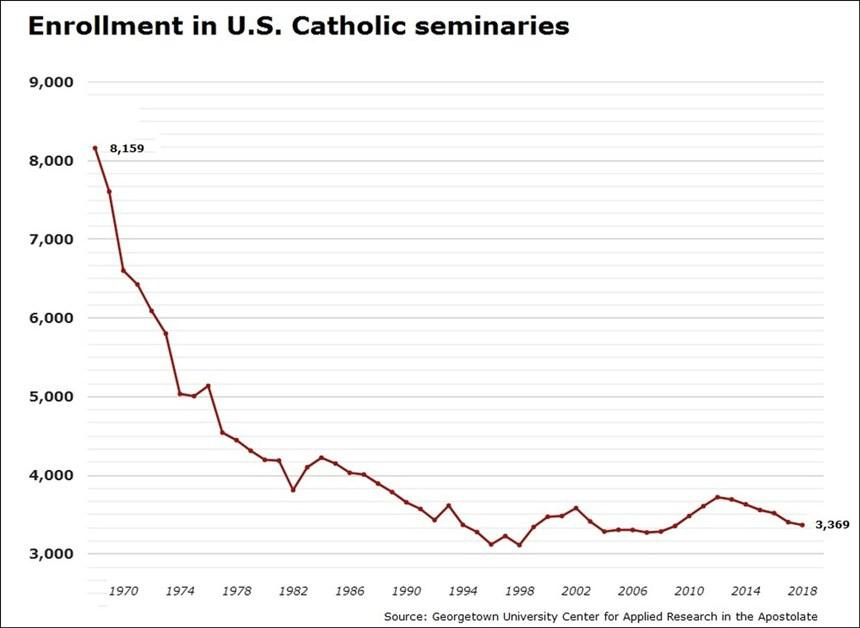

These next few charts encapsulate this as the real supercharger of the crises in the Church:

(Nota Bene: Not only do parishes have fewer priests, but they are also larger on average than they were in 1950, making the situation worse than merely returning to a 1950 status quo.)

Vatican II and the spirit thereof just crushed the numbers of priests and religious and led to a permanent decline in vocations, with no recovery in sight.

While lots of attention is put on the strain on priests and on religious orders from the massive declines they’ve endured over the last 60 years, and also on the closures of parishes due to these declines, having fewer priests per parish also has massive effects on the provision of the Sacraments, the ability of Catholics to seek spiritual direction from their priest, or their ability to have any meaningful relationship or pastorship over their flock.

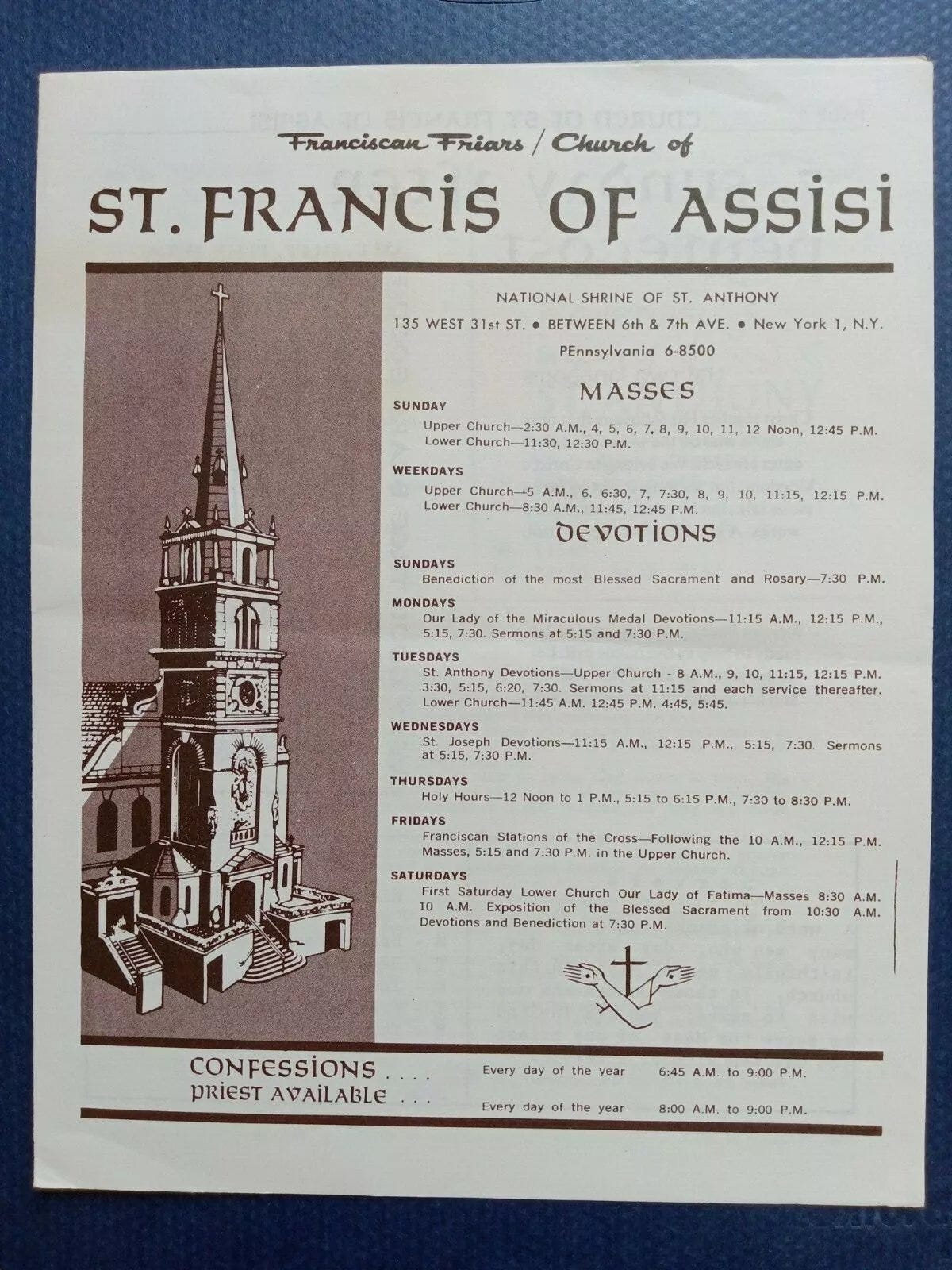

Compare this Church schedule from 1950, shared by Nico Fassino (admittedly in New York City), to those of an average, even large, parish today, and a key cause of the managerialist distraction and infiltration within the Church is evident.

There just aren’t enough priests to properly preach the Faith, offer the Sacraments, and keep the faithful in line, nor religious to assist them and fully carry out the mission of the Church.

Since there weren’t enough priests, they hired Susans from the Parish Council to ration out the time and priorities of those few who were left, to professionalize the Church to make it more “efficient” in response to the crisis, and to paper over lagging fervor with “transformation plans” and similar ideas from the secular corporate world.

It’s a vicious cycle where decline begets decline, and crisis begets crisis, papering over the cracks by replacing the life of the Church starting to show in the post-conciliar “New Springtime”, while making it far harder for those who do want to practice their faith to do so.

State of Necessity

The sad part about it, however, is that these managerialists and the solutions they proffer, as much as I decry them as infiltrators and the key cause of so many of the issues in the Church from the Council onwards, were kind of inevitable.

Catholicism in early 20th-century America had its flaws, infiltrators, and issues before the Council. But it was at least stable and on the ascendant. Vatican II, however, hit, just as a secular cultural change, the vast moves from the cities to the suburbs uprooted those very communities that supported thriving local ethnic parishes that had been built up from nothing over generations by Catholic fervor alone.

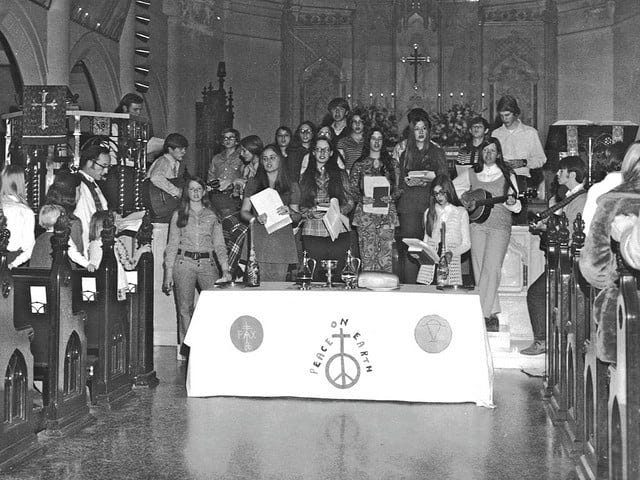

As Colleen McDannell recounts in her book The Spirit of Vatican II, the revolution in the Church can’t be separated from demographic changes in broader 20th-century society. As masses of people moved to the sprawl of the suburbs in the 1960s, new, distant, large, and less-local parishes sprouted up to serve them.

On its own, this isn’t a problem. The Church has adapted to serve new social conditions many times before. But these new parishes, not grounded in local tradition or community, were swallowing up many Catholics at the same time as the council was being implemented, and became, due to their rootlessnes, ground zero for many of the extreme novelties and banalities of the new liturgy and the new priorities of the “Spirit of Vatican II.”

The migrations of the 50s and 60s begat their own problems, creating a situation where neither the suburb nor the downtown (post suburbanization) is a complete society. Each is schizophrenically isolated and incomplete. People live in one, work in the other, and don’t have a true and complete love or responsibility 24/7 for both. Both call on systems and large-scale structures to replace freely working societal habits. Industrialization created the impersonal scale of human associations that justified managerialism and the managerial revolutions that swept the world culturally between World War I and the 1950s. Suburbanization and the accompanying scattering of human associations merely consolidated managerial holds on power, replacing natural culture with the mediated reality of misological marketing, cultural destruction, and extraction that has ruled the West since.

The parishes founded in this environment were no longer grounded in local tradition, clanship, or community. They no longer had a Catholic life for their pastors merely to guide and assist. Instead, in these new parishes, and at the same time as the council was “implementing” its changes and the sinews of Catholic culture were collapsing from lack of priests, religious, and motivated laity, the result was a one-two punch that reduced Catholicism as a faith more and more to merely Catholicism and the parish as an institution.

Furthermore, Vatican II also supercharged this trend by legitimizing it. Whereas active cooperation with secular governments would have been suspect at any time earlier in Church history, it was, under Dignitatis Humanae, merely cooperation for human fraternity, the bureaucratization of parishes, and the sidelining of their relationships with their people in lieu of a "parish structure” justified as “active participation”, “lay involvement”, and “anti-clericalism.”

Incorporate managerial methods, such as large staffs of laymen focused on “managing” various ministries or departments, and you subtly start to incorporate managerial ends. Success gets redefined from saving souls to the next budget cycle, to ensuring that there’s a baptismal process rather than baptism numbers, that there’s online engagement with the parish rather than retention in the faith, and from relationships with the saints and the Church’s tradition to relationships with the federal government.1

There are, of course, darker aspects to how this managerial aspect of the modernist revolution(s) came to pass. But many people who participated in the process that brought about “Diocesan Inc.” after the Council and which filtered out many of the most faithful members of the Church by inducing psychosis in many a faithful Catholic, thought that they were doing what they had to do in a “state of necessity” brought about by the declining metrics of the Church’s core mission.

Perhaps they were…

Managerial “Solutions”

There’s not really much you can do when you’re in a declining situation where you’re short on priests, and especially on one’s for whom true care of souls, in a system that rotates them around like machines and stifles any boldness in proclaiming as “dangerous.” Bureaucratic systems in parishes that make it difficult to receive the Sacramental help of the Church like what Sam Rhodes (Sam) commented on experiencing, are the end state of a long state of “managed decline”:

My diocese consolidated parishes and I could no longer go to my old pastor for baptisms for my kids. When my younger daughter was born, I approached the new pastor of the parish group and was told to go through the secretary who told me that I needed to take baptism classes and wait over a month along with pay a $100 fee to have my child baptized. When I protested that I never had to do this at my old parish, the secretary said that my old pastor broke the rules and she wouldn't make any exception. I asked to test out of the classes and she told me no that I had to take them. I went to the local SSPX and with some quick vetting they had my daughter baptized the week after she was born.2

Or as Amelia McKee described:

I have a friend who is trying to get her civil marriage convalidated by the church before her husband deploys. (He was raised Catholic and left the church for a while but has recently returned since having a son. She was raised Baptist and is in RCIA.) She was told that they needed to have their papers in 8 weeks before their meeting to SCHEDULE their con-validation. Neither of them were divorced prior to their civil marriage. In a church not overrun by managerialism, they would be able to go in and get their marriage convalidated next week.

I have another friend who is going through RCIA with her husband and family. Both grew up Baptist and are baptized Christians. They have six children and only the oldest is baptized. The youngest is five. She went to the church to request Baptism for her children and was told this summer that none of them could be baptized before Easter and that the older children may even have to wait until the next Easter. She and her husband have to go to RCIA classes every week until Easter for this to happen. She homeschools and her kids are better catechized than almost all of the other kids in the class.

I personally know the pastor, who even considers himself traditional, and have discussed these things with him, but of course, he puts his faith in his all powerful secretary who isn’t even Catholic. This is what managerialism looks like in practice. I have at least ten stories like this. People say Vatican II made it easier for the laity to participate. Really, it made the basic things, like obtaining the sacraments, much much more difficult.3

For many an average bishop, priest, or lay parish employee over the last 60 years, embracing managerialism seemed like the easy solution to making the crisis they didn’t want to admit what was happening go away.

It was, perhaps in their view, a state of necessity in these “Modern Times” that the old ways be replaced even the more with rational, managerial, and professional approaches.

Since success for the Church had already been largely redefined on purely managerial, that is, instrumental and process-focused, rather than purpose-driven (Sacraments, Faith, and Salvation) lines, this gave ever more power to the spawning Diocesan and Parish Industrial Complexes, which proffered managerial and business training for profit while sidelining anyone who objected to the spirit of the Council as a threat to what “had to be done” in the “state of necessity” of the Church

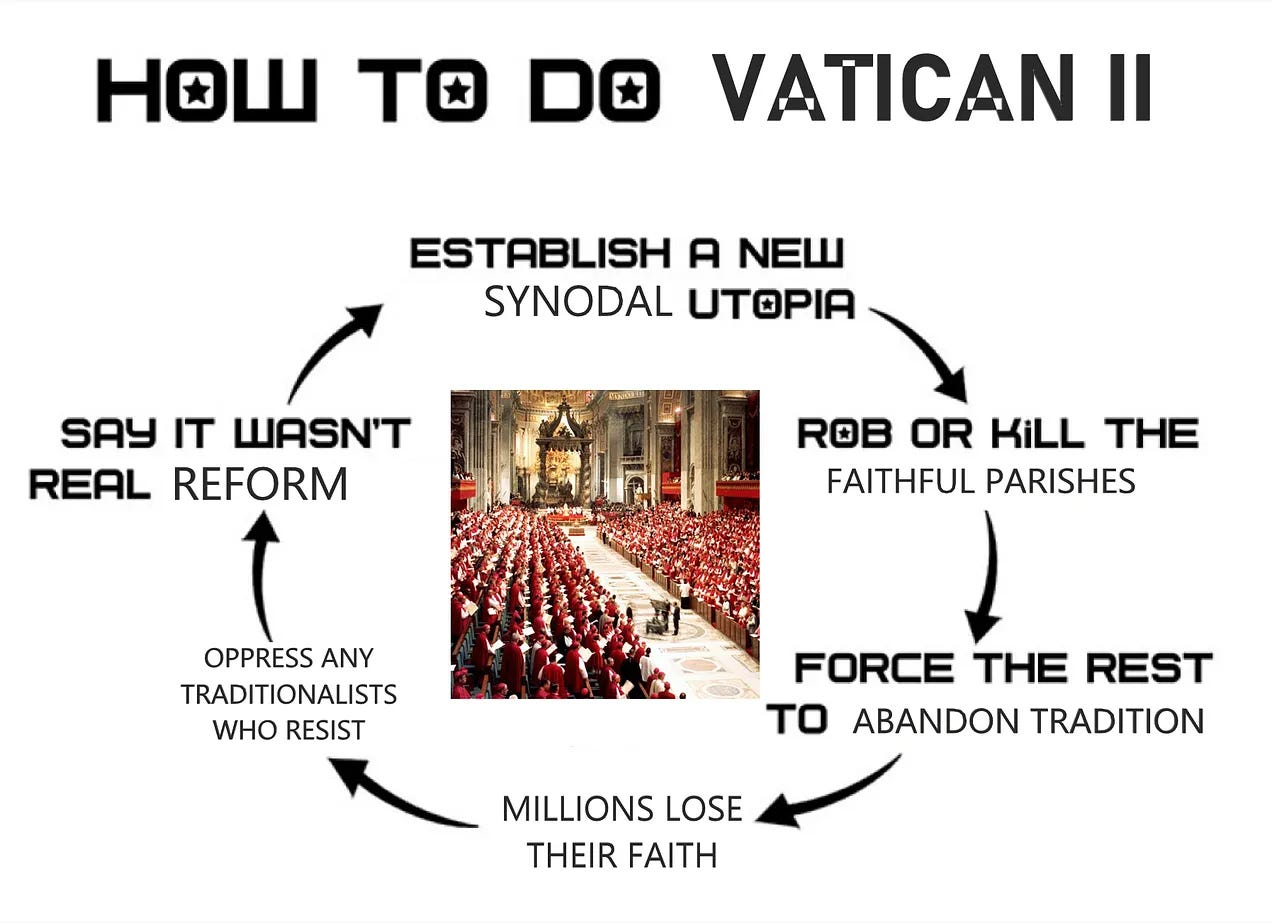

Darkly ironically, even though decline was baked into the picture by the same leaders who were turning toward managerialist and secularizing influences, they used that very decline as an argument that the revolution hadn’t gone far enough: Real reform hasn’t been tried yet. The Church is still too harsh on moral issues. If only we change x or start allowing y or give more power to lay institutions, or get government funding to support Catholic schools, etc….

Furthermore, the shortage of priests and religious, one, I believe, that was itself engineered, creates at least an apparent “state of necessity” itself. When there’s a crisis, even well intentioned bishops, clerics, and Catholic laymen are willing to accept a lot lower of a standard from their clerics, an environment where heterodox orders can receive approval if they bring wealth (and a supply of vocations), abusive priests and bishop get a pass, and looking too deep into scandals is scorned as dangerous to the institution. Lowering the standards due to a state of necessity creates new problems, however, that require new managerial solutions, such as vast court settlements due to victims of abuse, which only worsen the institutionalized distractions from the Church’s core mission due to the need to gin up more money.

A similar situation, of course, has hit the Church before. The 14th-century plague known as the Black Death disproportionately killed off priests and ministering religious, nearly 50% on average, with some areas losing 90%, creating a shortage of priests. To address this, the Church at the time lowered standards for ordination, advanced many less than qualified men to higher permissions, with an English Bishop even allowing, as an emergency measure, laymen to hear the confessions of the dying if no priest was available, with the long term trend that there was a less faithful and moral clergy, a Church more dependent upon governments and lay people, and a decline in the status and perception of the Church, already deprecated due to scandals of the Avignon Captivity of the papacy at the time. Within a few decades, this environment created the conditions for the crisis of the Great Western Schism, and within another century, this decline in the clergy cascaded to the chaos of the Protestant Revolution.

Our situation today is somewhat of a repeat of this period of crisis. The spiral of decay that began with a decline in the priesthood and religious orders after the council thus supercharged existing cultural trends, allowing, and then justifying the takeover of more and more of the Church by managerial methods and motives that have only further backfired into increased decline. Decline justifies the rule of those managing the decline by giving them a crisis to manage and an excuse for their own failures. Having a shortage of priests, while it’s been papered over for years with managerialist solutions to ration out the spiritual resources of the Church, is a primary enabler of the crises in the Church.

The primary question behind this decline, one that I will soon cover, is precisely why the religious orders and vocations to the priesthood declined so abruptly after the council, as so much of the other declines in the Church can be traced back to it. (The short answer: Psychologists, “Professionalization”, Drugs, and Blackmail, but more to come soon).

The managerial spiral of decline in response to the shortage of priests and religious focused on properly fulfilling the spiritual needs of their people has as its penultimate culmination, Fr. James Martin, who came from a “corporate finance and human resources” background but now serves from his high status near the Vatican as the ambassador and cheerleader for all things revolutionary in and outside the Church, preaching a gospel of good feelings in order to keep the Church’s relationships with the powerful in the world well greased.

For, with regard to Martin and those in the hierarchy who prop him up, the “state of necessity” today that justifies their power and the continued revolution is stronger than ever. The decline continues because no one wants their shallow bureaucratic product of platitudes, banalities, and meaningless marketing slogans.

Instead, they, like Amelia McKee, Sam Rhodes (Sam) and millions of others, want what the Church was established for: the Sacraments, the Faith, and Salvation.

This is the real state of necessity in the Church. Besides, of course, all the obvious practices one can perform on their own, it’s hard for those who want to practice their faith and want to be supported by the Church in doing so to do so. Service to God—and Salvation, are the ultimate necessities outside of which nothing else matters, so it’s no surprise that people, like Sam, look for alternatives to the regular, now heavily bureaucratized structure that seems determined to hold the Sacraments hostage.

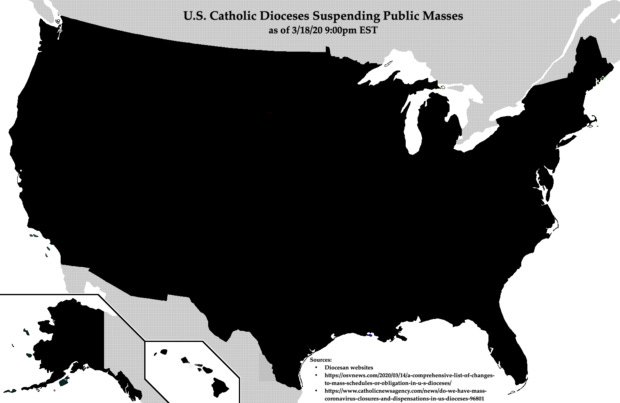

Especially so when the U.S. bishops, due to their tight cooperation with the U.S. government and their funding from it, all simultaneously chose to end the Mass and the Sacraments for several months.

While I have would I describe as qualms about the Society of St. Pius X’s (SSPX) position, especially regarding their pending new consecrations of bishops this summer, it’s hard to argue, given how dead set many bishops, priests, and lay administrators with power over parishes are on banalizing the Faith and holding the sacraments hostage for you to give a pinch of incense to secularism and modernism, that they’re not responding to a true state of necessity.4 Though most known for their defense of the Traditional Latin Mass, as without them we probably would have lost it and many other aspects of the Church’s tradition, they were founded, primarily, for the formation and support of priests.

Doctrinal heterodoxy and liturgical revolution are also important, but the decline in vocations to and the formation of those in the priesthood and religious orders, as Archbishop Lefebvre saw already in the 1960s,5 was a key supercharger of all the problems faced by the Church over the last century. I agree. I’m just glad I’m not the person forced to make the choice that their bishops and superior general, like Archbishop Lefebvre, just did. The SSPX, whatever they might do wrong, are trying to address this problem in a way that next to no other diocese or religious order is trying to do. Without them, it would be worse, far worse.

Even still, truly fixing the crisis requires more than they are doing, with smaller, more localized parishes where priests actually have a chance of knowing their faithful, a Church that is poorer, more independent, and less distracted by the bribes of secular powers, alongside a broader mimetic revival of the prospect and idea of the religious life and the priesthood, making it actually strike people as an option.

The decline in the number of priests and religious was truly a “second dissolution of the monasteries.” The key reason for how the modernist revolution of Vatican II and the managerial one thereafter succeeded was that it first destroyed a lot of the sinews of Catholic culture, the Catholic practice that would, and for a moment did, stand up to the revolutionaries. Like Stalin’s Holodomor and de-kulakization, the revolutionaries first went after the most successful in the Church, to ensure a state of dependence and shortages so that their revolutionaries would hold sway over those who remained.

Truly fixing the Church’s crises, no matter what else we do, requires addressing and reversing this, not by lowering the standards of the priesthood, or by making compromises with sketchy heterodox outfits that supply them, nor by stealing them from other countries, but by nurturing now the seeds of future religious and priestly vocations by at least not destroying them the way that so much of the managerial bosses within the Church seem so bent on doing.

No priests, or even too few of them, and no Faith.

I admit again that I have qualms about the SSPX myself, but I can’t argue that there isn’t a state of necessity that might justify their upcoming consecrations. Certainly, if there’s a state of necessity door wide enough to justify handing control of the Chinese Church over to the CCP, it’s also wide enough to justify quite a bit besides.

Dr. Eugene McCarraher, “Smile When You Say ‘Laity’: The Hidden Triumph of the Consumer Ethos”, Commonweal. https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/smile-when-you-say-laity:

Indeed, I recently learned that my own parish council is studying the “Total Quality Management” principles of the avuncular business guru, W. Edwards Deming, the Teilhard of corporate America. TQM is the most fully developed specimen of corporate therapeutics yet devised, replete with faux-zen aphorisms, hosannas to interrelatedness, optimization, and system, and lots of amiable psycho-noodling about flow. (Deming also refers a lot to Saint Paul’s notion of the Mystical Body, which becomes in TQM an exemplary model of corporate structure.) Now I don’t know if or how the parish council intends to actually use this stuff, but I think it suggests two things. Given opportunity by the priest shortage and legitimation by Vatican II, the professional-managerial laity now possesses a wrestler’s hold on the clerical imagination. Moreover, the laity who will be inheriting even more of the real power in the U.S. Catholic church are well-schooled in the therapeutic, increasingly “spiritualized” culture of corporate life.

As the SSPX’s Fr. Pagliarini has himself argued in explaining the Society’s decision to consecrate bishops: https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2026/02/interview-of-superior-general-of.html

See Bp. Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, Marcel Lefebvre: The Biography

You should transform all your articles into a hard-hitting but readable book that could be given to the faithful, the priests, and the bishops. If I was the publisher I would call it “The Bad News: What We Have to Accept (and fix) to Get Back to the Good News”

Thanks for this thoughtful article. To be fair, that Franciscan church in NYC was an outlier back then, even among city churches: probably dozens of active friars lived in the attached residence. The OFM place in Boston was also a "factory" with 31 Masses each Sunday in 1980; now only five. Three smaller Franciscan "worker chapels" in Boston, Providence, and New Bedford were given up by the order. That story of collapse, with the disappearance of numerous city religious-order churches and chapels, is worth telling, but it's distinct from the collapse of general parish life.